WHEN WILL LAGOS TAKE WATER SERIOUS?

When it rains, they say it pours. In most parts of Lagos Nigeria, when it rains it doesn’t just pour; the pouring comes with flood. According to experts, Flooding defines “a condition where wastewater and/or surface water escapes from or cannot enter a drain or sewer system and either remains on the surface or enters buildings.”

Surcharge is “a condition in which wastewater and/or surface water is held under pressure within a gravity drain or sewer system, but does not escape to the surface to cause flooding.” Flooding in urban areas due to the failure of drainage systems causes large damage at buildings and other public and private infrastructure. Besides, street flooding can limit or completely hinder the functioning of traffic systems and has indirect consequences such as loss of business and opportunity.

Living in Lagos, it is easy to erroneously think that the flooding affects only the areas close to coastal shores, the Islands and the slums. But the floods have proven to show themselves in places which are quite far from the Atlantic, and feel cannot be touched on the Mainland. With the incessant inundations experienced and Lagos being a coastal city, many view the city as beneath the sea-level or even at par with the surrounding waters of the Lagoon and Atlantic Ocean. But Geophysical surveys has shown clearly that Lagos is not close to that at all; one of the Islands of Lagos is about 41m above sea-level; while Lekki, another Island, having had some parts of its bay sand-filled and lands reclaimed some decades ago to expand the shores, is about 5m over sea-level.

So, what is Lagos doing wrong? How can we get the issue of this recurrent flood right? How can Lagos survive the waters?

To answer this germane inquiry in the best way is to look at some other coastal cities in the world with nearly identical geographical features with Lagos, facing same challenges, and how they’ve hurt, learn, and overcome what being a city close to large waters consistently throws at them.

We will glean at these 3 following Coastal Cities and see their story:

1. BAKU, AZERBAIJAN

A relic of the past and the hope of the coming future in the Land of Fire. Baku is the capital and largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and of the Caucasus region. The city is located on the southern shore of the Absheron Peninsula, alongside the Bay of Baku. At 28 metres below Sea-level, this makes the city the lowest lying national capital in the world, and also the largest city in the world located below sea level.

Despite Baku basically having had some parts of it gradually submerged by the ever expanding Caspian Sea year in year out for over 500 years, the City has learned to evolve over the years to ‘weather the storms’ and the rains with the floods, and are still going strong. Baku also renowned for its harsh winds, which is reflected in its nickname, the "City of Winds", has shown clearly that humans will prosper wherever they are with tenacity, consistent planning and execution to surmount the environmental challenges that faces them and flourish.

How does Baku solve its water problem?

This is a city that knows excess water in its lithology means serious problem for the citizens and constant heavy flooding. In the 1930s, the main pipelines and water disposal facilities were built and designated for use in Baku. “Baku Sukanal” Department, a Government parastatal created to oversee water management in Baku, has 13 central water reservoirs with total capacity of 949.2 thousand m3 in the official area. The length of transmission and distribution lines is 4,703 km; sewerage network is 1,486 km length. Department renders services to 6 wastewater treatment plants and 44 sewage- pumping stations. The Azerbaijani Government are always conducting advance research on the hydrogeology of the city, to see how they can manage their underground water level, and also the wastewaters produced with their drainage systems. And different types of the Drainage systems have been employed and implemented throughout the city.

In the sewerage sector, Baku wastewater network serves 72% population of the city, but only 50% of the water is treated. 90% of the treated water is biologically processed and only 10% is mechanically processed. Even though in most cases, the quality of water supplied to the population does not meet the required standards. The state works with donor communities to take the necessary measures to address these problems. The state on May 9, 2020 launched another 12 project to tackle the Rainwater Drainage System and at the same time, local water supply projects are being implemented.

On Sunday, 23rd September, 2018, bad weather of biblical proportions that struck the city of Baku, as heavy rains flooded the city centre while a mud volcano violently erupted on its outskirts, producing a pillar of fire and smoke. Baku’s mud volcano Othman-Bozdag on that day sent flames and smoke as high as 200-300 meters in two consecutive bursts.

A statement by the Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources said the rare event was still in full swing. The ominous sight came as torrential rain struck Baku in the early morning. Water quickly flooded the city’s main streets and avenues as well as some metro stations, social media images and local media reports showed. And even after all these had happened, the citizens remained calm and didn’t suffer any loss of lives, because they had already had a plan on ground to tackle this problem, always working on their drainage systems, never joking with their surrounding waters.

A city prepared to handle anything thrown to it by the forces of nature is a city that will continue to prosper in spite of every environmental hazard faced.

2. AMSTERDAM, NETHERLANDS

The city nicknamed “Mokum”, which means “The Place” or “Safe Haven” in Yiddish, Amsterdam is the capital and most populous city of the Netherlands. Found within the province of North Holland, Amsterdam is colloquially referred to as the "Venice of the North", attributed by the large number of canals which form a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Topographically at 2 meters below the Sea-level, water has been in Amsterdam’s lifeblood since the city’s inception.

In the 13th century, after decades of disastrous inundations by floods and storms, the people of the Amsterdam started developing strategies and technologies to deal with flooding. Water management innovations, such as the now-iconic 15th-century polder windmills, which pumped out swampy areas, often lying below sea level, proliferated. Over time, some 3,000 polders, or dryland plots surrounded by dikes, were created. Also, the canals were built; allowing the city to move goods by water instead of horse and cart and through that become one of the world’s greatest trading cities. Amsterdam has more than 100 kilometres (60 miles) of canals, most of which are navigable by boat. It has been compared with Venice, due to its division into about 90 islands, which are linked by more than 1,200 bridges.

Flood control is an important issue for this city. Natural sand dunes and constructed dikes, dams, and floodgates provide defense against storm surges from the sea. River dikes prevent flooding from water flowing into the country by the major rivers Rhine and Meuse, while a complicated system of drainage ditches, canals, and pumping stations (historically: windmills) keep the low-lying parts dry for habitation and agriculture. Water Control Boards are the independent local government bodies responsible for maintaining this system.

“The Netherlands as a nation was born fighting the sea. The DNA of Holland is to live in a delta, to live on the coastal plain and to live in the swamp. The entire Dutch culture is born from this notion.” - Adriaan Geuze, founder of the Dutch design firm West 8.

The Dutch became famous for their early mastery of coastal engineering and water management which for centuries largely kept them safe behind barriers and dikes. But this sense of safety was sharply battered in early 1953 when the North Sea broke through the protections, flooding more than 2,000 square kilometres of land and killing 1,835 people overnight.

After the flood, the Dutch redoubled their efforts to battle the sea, creating an enormous flood-control system known as “the Delta Works.” A modern engineering marvel, it consists of nine dams and four storm barriers that have closed off estuaries and substantially reduced the Dutch coastline by about 700 kilometres. It was also during this time that they came up with the Vertical Drainage System to deal with precipitation the city receives from the rains, and serious treatment of wastewaters from the citizens of the city. Delta Works has served the Dutch well for decades, but extreme flooding in the ‘90s caused mass evacuations and fuelled rising concerns about climate change and sea-level rise. Dutch water managers saw limitations to “hard engineering” approaches like dikes and barriers in a rapidly changing and increasingly unpredictable climate, so they took a vigorous new approach.

In addition to their “hard engineering” approach, the Dutch also began applying a more long-term, holistic perspective about flooding that considered scientific data about the changing climate. The crowning achievement of this costly effort is known as “Room for the River”, a massive $3 billion project initiated in 2006 that involves some 40 different infrastructure projects along Dutch rivers and waterways. At the heart of the project is the idea that instead of keeping water at bay, space can be allocated to safely accommodate flooding. Dikes and other obstructions are removed, and flood channels and floodplains are broadened and deepened.

This was what Chris Zevenbergen, Professor of Flood Resilience of Urban Systems at the IHE Delft Institute for Water Education in the Netherlands said when asked about the innovation,

“At the moment, we are in a transition. We had a strong belief that we could predict and control nature, and we're moving now into a period where we acknowledge that we cannot control nature. We have to deal with uncertainties in terms of climate change and socioeconomic development.” -

Eventually, (and this took centuries) the Dutch continue to learn, execute plans and evolve; seeing the protection of Amsterdam as part and parcel of protecting the whole country, creating different approaches from Engineering to creating smart cities alike. And it seems to have worked. The Dutch have even turned flood protection into a business; exporting what they’ve learned to help other countries deal with their water problems. Now if that isn’t making lemonade out of the lemons the surrounding waters and rains have given them, I don’t know what is!?

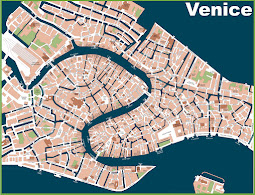

Up in the northeast of Italy is the city known as "La Dominante", "La Serenissima", "Queen of the Adriatic", "City of Water", "City of Masks", "City of Bridges", "The Floating City", "City of Canals"; Venice, the capital of the Veneto region. Topographically at barely 1 meter above the Sea-level, the city is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges in the Adriatic Sea. It has no roads, just canals – including the Grand Canal thoroughfare – lined with Renaissance and Gothic palaces. The central square, Piazza San Marco, contains St. Mark’s Basilica, which is tiled with Byzantine mosaics, and the Campanile bell tower offering views of the city’s red roofs. The islands are located in the shallow Venetian Lagoon, an enclosed bay that lies between the mouths of the Po and the Piave Rivers (more exactly between the Brenta and the Sile). The lagoon and a part of the city are listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In its many centuries of existence, and being proud to be one of the cities of Europe to have domiciled some of the greatest minds of the human race since the Renaissance period, it is in no doubt a great achievement to see this great City of Water still standing tall after so many centuries.

So, how is Venice coping with the Floods?

Floods have been a part of life in Venice since its inception. In the 5th century, refugees who fled from invaders came to this collection of boggy islands off of the mainland. In order to build, they drove a huge number of heavy wooden piles down into the mud to create a foundation. As it happens, the muddy marsh is not the most stable place to build, and the city has always been subject to the fluctuations of the lagoon ecosystem. Since this time, Venetians have been locked in a battle with the tides. Yet this fragile balance that Venice lived in was broken in the 20th century.

In 1918, building began for a huge industrial complex at Marghera, on the edge of the lagoon. Marghera became home to many chemical plants and petroleum refineries, which dumped their highly toxic waste directly into the water. Deep channels were dug out to accommodate the large industrial tankers coming in. The powerful currents created by these boats began to wash away the lagoon floor into the ocean. Meanwhile, the vegetation on the floor of the marsh is being killed off by water pollution, which further reduces any ability to absorb turbulence. Reclaiming land for big building projects such as those at Marghera, Marco Polo Airport, and the Tronchetto car park also played a role, as those mudflats had served to dissipate the strength of the waves coming in. And perhaps most detrimental of all was the pumping of groundwater from aquifers underneath Venice to support local industry. This was banned in the 1960s, but the damage could not be undone. The wood foundations of Venice could last for centuries, but they were not built to withstand the intense waves created by motor-powered boats, especially when it comes to the huge cruise ships that come through the Grand Canal. These monstrous vessels dwarf even the largest buildings in the city, and their mass creates waves of turbulence that can last for hours.

On November 4, 1966, the city of Venice woke up in the middle of its biggest nightmare. An abnormal occurrence of high tides, rain-swollen rivers and a severe sirocco wind caused the canals to rise to a height of 194 cm above median sea level and covered almost the entire city. The tide remained for 22 hours above 110 cm and for about 40 hours over 50 cm. Although Venice is known for its acque alte or high waters which often flood the streets, this flood left thousands of residents without homes and caused over six million dollars’ worth of damage to the various works of art throughout Venice, making it the worst flood in the history of the city.

After being neglected and quietly deteriorating ever since the defeat of the Venetian Republic by Napoleon about a century and a half prior, Venice was suddenly recognized as a city in urgent need of restoration. Funding and assistance came from all across the globe as the tragic event reminded many of the need to preserve Venetian art and architecture. Funding was received from different World Organizations for rebuilding, and restructuring, and Venice has since then never looked back for so long, or so the Venetians thought.

In continuous effort to preserve the beauties of Queen of the Adriatic, after decades of debate, a project called the MOSE (Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico, Experimental Electromechanical Module) was inaugurated in 2003 to protect Venice by then Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi. The name is shortened to MOSE because it means Moses in Italian, the biblical man who parted the Red Sea. The project is an integrated system consisting of 78 enormous steel boxes, rows of mobile gates, installed at the Lido, Malamocco, and Chioggia inlets that are able to isolate the Venetian Lagoon temporarily from the Sea during high tides. Together with other measures, such as coastal reinforcement, the raising of quaysides, and the paving and improvement of the lagoon, MOSE is designed to protect Venice and the lagoon from tides of up to 3 metres (9.8 ft). The Consorzio Venezia Nuova is responsible for the work on behalf of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport – Venice Water Authority. Construction began simultaneously in 2003 at all three lagoon inlets, and by 2013, more than 85% of the project had been completed. After multiple delays, cost overruns, and scandals resulted in the project missing its 2018 completion deadline, it is now expected to be fully completed in 2022.

On November 12, 2019, the second highest water level on record--1.87 meters (6.2 feet)--inundated over 80% of the historic city. Photographs and videos spread across the world showing the city’s iconic Saint Mark’s Square was inundated by more than one meter of water, while the adjacent Saint Mark’s Basilica was flooded for the only the sixth time in 1200 years. As at the moment, work is seriously going on the MOSE project, so as to meet the deadline and prevent yet another great flood like 1966 and 2019.

The beautiful city of Venice has always been threatened by the Adriatic Sea, but this has not removed the city from its roots. By 2022 when the MOSE project will be completed, the flooding from the Adriatic high tides will be a thing of the past. The Venetians after many years of troubles with water have come to count their losses, wounds and even turned them into blessing. La Dominante is a proud owner of one of the best Inland Waterways Transport System in the world called Vaporetto. These water bus take people, tourists and indigenes alike, from one corner of the city over the canals to another in their spacious elegant designs.

Amongst the top ten most beautiful cities in the World, Venice is one. This is a city constantly threatened by the sea, but still never surrenders its beauty.

Now that we have delineated these three Cities, you will see that they are not in any way perfect. In fact, they are geographically disadvantaged against the forces of nature. But through time, consistent work, learning and perseverance in their planning of their waterways, execution of legislation, drainage systems and hard engineering, they have continued to wax stronger and dominate their environment. In contrast, Lagos is a city not threatened by the high tides from the Atlantic Ocean; we are not below sea-level as far as topography is concerned. In fact, we are at a considerable safe elevation from a major flooding from the Ocean.

So why are some parts of Lagos always plagued annually by these easily preventable floods?

We can only get an absolute answer in how we treat our waterways; the drainage, the canals, and trenches scattered all over the city. The internal drainage systems in the city are not sufficiently planned or even well maintained; they are not large and deep enough to contain runoffs from the inundations, especially on the Islands like Victoria Island, Lekki and Ikoyi. The many canals which serve as conduits for the runoffs to pass and be emptied into the Lagos Lagoon and the Atlantic from the mainland are not well dredged and cleaned of the constant human refuses dumped into them. Some of these canals pathways are blocked by people in slums who built on them. And this causes the surcharge after serious downpour to be very low, causing flooding every time. There is a need to go back to the drawing board and start this treatment of this problem from the scratch.

Lagos, like Venice and Amsterdam, is blessed with considerable amount of water channels in canals from the inland to the Lagoon and the Ocean.

(Map of Venice vs Lagos)

Why are we not thinking about dredging, expanding and interconnecting them, making them navigable by boats as Amsterdam and Venice? If we can work on these first, find ways to curb the city dwellers to stop dumping their refuses into the drainage through actionable laws and sanctions, and considering some “hard engineering” approach, the flooding will automatically be removed from the major problems constantly facing the city. Then there is a need to focus on hard engineering approach to solve the constant overflooding that bewitches the Lagos Islands just as Amsterdam had done in protecting their lands close to the coastline. Lagos is topographically favoured, a quite good elevation for a coastal city, and littered with veins of water channels that can help reduce the outflow of inundations and easily serve as yet source of revenue for the Government.

When will Lagos take Water Seriously?

Well…the ball is still in our court, gently waiting to be played.

Well researched and well written! Thanks!

ReplyDeleteGreat research. Kudos

ReplyDelete